Mountain Bikes Should Not Be Allowed in Wilderness. Let’s Find a Solution

I love the outdoors — I thoroughly enjoy cycling, mountain biking, hiking, and any other excuse for getting outside and wearing myself out. My interest in mountain biking has also grown recently, since my time is limited now that I’m a parent, and biking presents an opportunity to get out on little adventures more rapidly. There is however a place for enjoying such adventures, and designated wilderness isn’t the right place for mountain bikes.

A bill was recently introduced (HR 1349) that would allow mountain bikes into designated wilderness areas — places where bikes haven’t been allowed previously, and where hikers are able to enjoy quiet, solitude, slow travel, and being able to fearlessly walk without fear of being hit by a bike.

There is a trail near me that I enjoy, but it’s also popular with mountain bikes. It definitely is less enjoyable fearing someone flying around a corner, or getting out of their way as they come screaming past (it’s even worse when they come flying up from behind). It’s OK though, it’s not wilderness so I accept that when hiking there, but it’s nice knowing there are places I can go where I don’t have to worry about it and where I can let my guard down and just enjoy nature. I personally would be pretty devastated if I lost that.

How Much Land is Available to Mountain Bikers and Hikers?

For many hikers, the wilderness does represent space to walk freely, quietly, and without the worry of being startled (or hit) by someone on a bike. It’s a peaceful place where we can slow down, drop our anxiety levels, and enjoy the quiet.

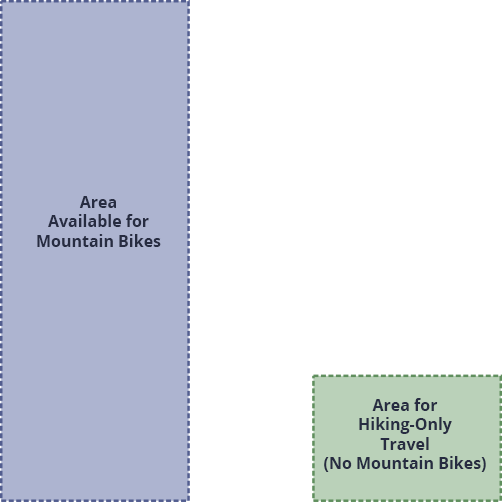

With perhaps a few small exceptions here and there, bikes are allowed on National Forest Land outside of wilderness areas, which equates to about 80.6% of the land in the US Forest Service system. For those looking for a true wilderness hiking experience without bikes, we are currently left with the remaining 19.4% of the land area to enjoy. There is so much land already open to mountain bikes, that I don’t understand the desire to take away these quiet hiking areas from that user group. It does seem a bit selfish for the group of people who can have their run of 80.6% of the land area, to want access to the remainder as well, and in turn, take those areas away from those looking for true wilderness.

The graphic above displays how much land administered by the US National Forest Service is available to mountain bikes (blue – 80.6%), and how much of their land is set aside as wilderness and foot-only travel (green – 19.4%). The “fair” thing to do, according to the mountain bikers is to take away the only land available for foot-only travel, and give them access to 100% of the land, leaving hikers with no land where they can enjoy a true wilderness setting.

The Encroachment of Civilization

A basic idea of wilderness is that it is removed from civilization. We bring a bit of civilization in whenever we walk into a wilderness area, but the further you push, the more crowds thin, and the more you enter the realm of the quiet and pristine. On a typical backpacking trip, I generally aim to hike around 15 to 20 miles, which generally takes me all day. On a bike, those distances are reduced to a matter of hours. On a trip where I’ve spent two or three, even four days hiking from the nearest road to find solitude, a biker could easily set up lunch next to me with a sandwich they picked up that morning, and be back in town within a matter of hours to grab their post-ride beer and burger. That place where I set up my tent to find some peace and quiet, can now be easily accessed by numerous mountain bikers out on their daily trips.

There are very few places that offer a chance to remove ourselves from civilization — and we should be working to make wilderness even further removed, not more accessible. We need places to escape — places that are hard to get to and require time and effort.

Overuse

The above image is a beautiful lake-filled meadow below the glaciated north face of Mt. Jefferson, known as Jefferson Park. It’s a full-day backpack for most backpackers, which naturally limits the amount of usage to this already popular area. A person (or many people) on this bike could reach this same area in a matter of hours. We are already beginning to limit the amount of people permitted access to wilderness areas. It’s necessary, but at the same time, it’s a bit of a shame. While we definitely need to be enacting quotas, perhaps the easiest method for minimizing the strain on our wildlands is to keep them strenuous to reach; which means travel by foot, not wheeled bikes (or even worse, electric mountain bikes).

A Plan to Move Forward

Mountain bikers and hikers probably agree on 95% of things. We are not enemies (some exist in both worlds), and we should work together so we can all be happy, because I’m sure there is a way forward. In short, I think hikers and bikers should team up to help build more trails for everyone, with some designated as only for mountain bikes. I think a good action plan could be:

- Massively expand trail systems outside of wilderness areas for mountain bikes and hikers.

- Designate mountain bike-only areas and build out trails for mountain bike-only use. Perhaps even aim to build the same amount of trail mileage for bike-only use that is contained within wilderness.

- New Designation for “Quasi-Wilderness” – If some percentage of trails (10-15%) within a proposed wilderness area have been built by mountain bike groups with the cooperation of the forest service, those areas should be reviewed for the continued use of mountain bikes in the “quasi-wilderness”. Perhaps even all new wilderness designations should be reviewed (but unlike the current bill, let’s leave the existing wilderness areas as they are). Perhaps it’s a mix of some trails within these wilderness areas allowing bikes, but others not.

We’re all really looking for the same thing — places where we can enjoy our respective activities to the fullest extent. I think it’s only fair that we should provide more opportunities for mountain bikes, but we need to look at the desires of all groups. We are all part of the outdoor community, and we should work together to find solutions that we can all be happy with.